Where the Autopista Ends

Two motorcycle bloggers in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Life on the road

Posted on December 16, 2013

With only a few days left in Nicaragua, Alex and I were reviewing the timeline before we battled our way through another border and on into Costa Rica. We decided that we wanted to spend a half day in Granada before moving on to the border.

Granada is a lake town that sits on the edge of Lago Nicaragua, with views of Concepción Volcan in the distance. We would have pictures of all of this, but there was another unfortunate motorcycle hiccup. As we pulled the motorcycles into our hotel in Granada (Hotel Casa Barcelona, a hotel that promotes jobs for local women to become independent bread winners) Alex felt/heard a snapping sensation in her clutch cable, lo and behold we could see that of the nine or ten strands of cable, all but three had snapped.

Alex shows off the damage after pulling the frayed clutch cable out of her bike. Photo: Alex Washburn

Before I could protest, Alex was out of the hotel lobby and into the courtyard, borrowing a pair of pliers from the hotel handyman (Giovanni, he will be in the story later) and beginning to rip into the clutch lever. The only conversation we had on the subject, was whether we thought the bike could make it in its current state to the shop we are going to in Costa Rica. Upon further review we both decided it would be foolish to continue without some sort of repair.

In about thirty minutes we had dissembled the clutch lever and removed the clutch cable. Alex held it out to the two handymen that were working on staining a table in the courtyard where our bikes were. Giovanni came over to inspect the cable, and Alex asked where we might be able to obtain another one.

By now it was 4:00, and the main concern was that if we didn’t find a replacement, most of the shops would not be open on Sunday and it might mean a delay of several days to get it repaired. Giovanni said he knew of a shop and suddenly we were in his car racing through Granada.

It was at this time that the sky’s let loose the rain they has been threatening all day and monsoon style downpour drenched the tiny town as Alex and Giovanni sprinted into the shop. The full cable assemblies they had in stock were too short by only a couple of inches, so we ended up getting a long replacement cable to feed into the tubing of the original.

Back to the hotel we went, the rain went just as quickly as it came, and though the bikes were wet, it didn’t slow the installation. Giovanni provided a helping hand in getting the new cable threaded and hooking the clutch lever back up. Next we needed to attach it to the motor. Here we ran into some problems because the washer and bolt that came with the replacement cable were too big to fit into the housing on the motor.

Giovanni pulled out a grinder and started shaping the nut to fit. A little bending to widen the housing, and we were able to get the nut into the system. A little adjustment at the lever, and it was good as new or at least jimmy-rigged enough to get us to Costa Rica. It wasn’t pretty, but it meant we could stay on schedule and get across the border. It took all the time we had in Granada to do it, however Alex’s faith in us being able to fix it was unwavering, she amazes me!Also, as in Honduras, when we needed help, the right people seemed to show up. We are grateful that Giovanni was so willing to help two strangers and are still amazed at the kindness of strangers here in Central America.

The following day came early and it was time to see if the cable would hold and what the border had in store for us. The border crossing wasn’t the worst in terms of harassment, but was the most extensive in paperwork and general futility. All told it took five hours.

Nicaragua had the most amount of work to exit a country yet. Most countries are glad to let you go with a stamp and some well wishes as you become the next country’s problem. However, Nicaragua required we have an official (who is wandering around the immigration area) inspect the bikes, then we had to get a stamp from a second of official in a booth, before tracking down a police officer (who also is just wandering around) to sign our forms. It took two hours just to get all the paperwork filled out and signed just to exit Nicaragua. For comparison, exiting Honduras took all of twenty minutes.

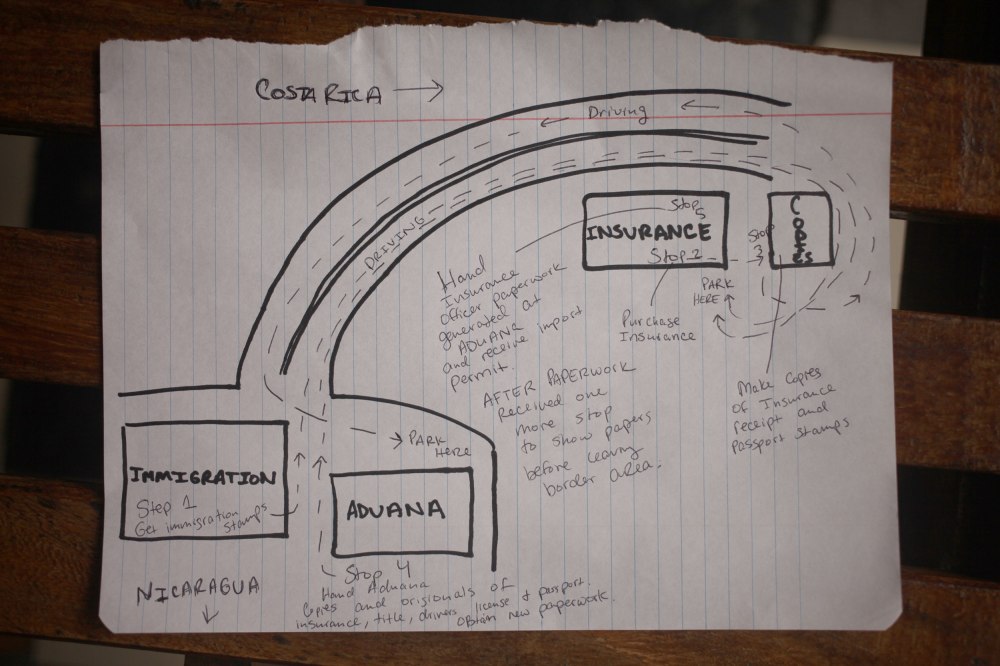

Next it was on to Costa Rica. Instead of describing the whole procedure, we have drawn this diagram:

After five hours of border crossing hi jinks, which included the insurance agency typing Alex’s VIN wrong three times, we made it into the countryside and all the way to Liberia Canton for a victory dinner. Country number seven is ours for the taking, and we are off to San Jose for our appointment to have some much needed maintenance done to the bikes.

Volcano Boarding

Posted on December 13, 2013

We climb into the back of an absurdly large giant four wheel drive truck with other travelers from the UK, Israel, Germany, Ireland, Australia, Holland and the United States; we all fidget with nervous energy grinning and waiting for our adventure to start.

The truck fires up and lurches off throwing us into one another as it rounds corner after corner, bumping along on small cobblestone roads in a way that would make veterans of the Knight Bus nervous (Harry Potter reference).

There are no seat belts and we grab onto the railings, seats, and each other for stability during the 45 minute ride to Cerro Negro.

About a decade ago an Australian with presumably too much time on his hands visited Leon Nicaragua and decided to turn the active volcano Cerro Negro into an extreme sport destination. He first tried boarding the hill with a snowboard and destroyed his equipment in the process — volcanic rock is not kind to fancy gear. Next he tried a refrigerator door (fail), before moving on to a picnic table (also a fail), a mattress (biggest fail) and a variety of other items he thought might make it down the 42 degree slope of black volcanic rock.

Today in Leon there are several companies that offer volcano boarding tours down Cerro Negro and although the protective gear varies slightly from company to company the boards they use are all the same. A one foot by four foot piece of plywood with several wooden slats across it and a rope handle you hold like a baseball bat can be found on the top, on the bottom a plank of thin metal and a patch of formica held on with adhesive provide your sliding surface. The thrill of sliding down an active volcano wearing prison jump suits while sitting atop construction scraps is what brings our collection of world travelers to the back of this obscene vehicle.The cobblestones quickly gives way to cracked pavement and then dirt. The driver rushes over the small roads kicking up a mountain of dust that engulfs bicyclists, cows, pedestrians and entire busses as he rushes past and the road just keeps going.

Local guides claim that because of the wind patterns in the area Cerro Negro is the only volcano in the world suitable for Volcano Boarding. This may or may not be true but a google search for ‘volcano boarding’ will only give you hits related to Leon Nicaragua.

We pull up to the entrance of the nature park and slide to a stop. We all have to pay a $7 entry fee to enter the park and sign our names in the visitor ledger before we ride the last few kilometers to the base of Cerro Negro.

Cerro Negro isnt impressive looking because of its size, although it feels massive to hike up carrying a piece of metal sheathed plywood and your obligatory jump suit. No- Cerro Negro impresses with its dramatic slopes of black rock. Nothing grows on it and at the top you are greeted only by the smell of of sulfur and the giant bugs that are drawn to it.

Our guide Jose gives us a quick rundown of what to expect on the hike, how to best carry our board and tells us that we will stop three times along the way for information and to rest — we begin.

The hike starts easy enough on roughly shaped steps made out of larger rocks the size of your head, but as the slope gets steeper, the rocks get smaller, and the wind picks up hitting your board like a kite, it can get scary. We creep along the side of the volcano stopping and posing for photos when Jose tells us to and gripping the boards for dear life as we march up the path.

The real tragedy would be falling off the path, losing your board, and doing the hike for nothing. It takes an hour to climb the Volcano and less than a minute to slide down it, less than 30 seconds if you’re going for a record or are interested in seriously hurting yourself.

At the top we take time to appreciate the view and Jose scuffs a mark into the dirt and has us feel the earth just a few inches below the surface, surprisingly it is almost too hot to touch and you can see a few people’s faces questioning the sanity of sliding through it wearing a cotton jumpsuit and flimsy plastic goggles.

I am already wearing my goggles because it’s so windy at the top of the volcano little bits of rock and dust keep flying into my face. I don’t care if I look silly – I’d rather not blind myself before the ride.

Jose gives the command to ‘SUIT UP!’ and the moonscape at the top of the volcano gets even more bizarre as a dozen tourists start pulling on orange jump suits and goggles, a prison gang run wild. I ignore the command (sorry Jose) and buzz about taking photos of people getting ready as Jose starts his safety speech.

The single rider speed record on Cerro Negro is over 50 mph. When you consider you aren’t going to be wearing gloves or a helmet as you slide down a hill comprised solely of volcanic rocks, then listening to Jose when he gives you safety instructions is key. However – I’ve done this before and I have no desire to break a speed record.

Last year a couple decided to race down the hill and the boyfriend lost control of his board and hit his girlfriend, breaking her back. A few weeks ago another tourist on vacation with her family lost control at a high speed and broke her leg and foot in several places, stories Jose doesn’t share till we are all at the bottom. It’s scary – but the same things could also happen while snowboarding.It’s at this point I wrap my 5D Mark II in plastic with my iPhone and stick it in my backpack before pulling the jump suit over it. We take our places in two lines as Jose issues his final instruction before disappearing over the lip of the volcano to take pictures of us as we board down.

Several people take their turns and then suddenly it’s my turn. I carefully position myself on the board as I try and center myself in the starting chute while Nathaniel looks down at me with his GoPro.

The signal is given and I start scooting myself to the edge. I have problems getting out of the chute (the guy before me did it too fast and fell off his board), but once I hit the slope I start to slide easily down the volcano.

Gripping my rope I think I am going too fast so I dig my feet in, but I can’t seem to slow myself down. Once I reach Jose I know I am not allowed to brake anymore because the slope becomes too steep to safely slow yourself down. One of Jose’s biggest warnings at the top:

Once you pass me do NOT try and brake. 45 degrees is too steep to brake on, you will lose control and it will hurt.

The adrenaline starts to pump through me and I am reminded to keep my mouth closed as I taste the grit flying into my teeth. I clamp my mouth shut as I slide past Jose and then I lift my feet. I can use them to steer still – letting my motorcycle boots carefully skim the surface of the volcano, but I resist the urge to bury my feet in the rock.

I can feel the friction heat up the board underneath me and I wonder to myself if something could catch fire with that much heat. My speed starts to increase as pure gravity and the formica slicked board do their work. I start to hop slightly over a few bumps and for a second I think I am going sideways – rushing past our secondary guide who holds a speed gun I safely come to a stop.

Nothing moves.

I stand up, careful to pick up my board by the rope (the board is now hot enough to burn you) and I give my guide my name ‘Alex’ so he can record my speed. I join the others at the truck and start to strip off my jump suit watching the next few people make their way down Cerro Negro.

Once everyone has made it to the bottom we watch in awe as Jose runs down. He passes out our beers and takes a celebratory photo of all of us before we climb back on the truck for an even crazier ride back to our Hostel. At the hostel all volcano boarders are given a free mojito, most people caked in black dust gulp it down and make for the showers.

These are the days that make travel worth it.

Tegulcigapa (again)

Posted on December 7, 2013

Storm clouds approach as two mechanics in a town we don’t know the name of work to get both our bikes back on the road. Photo: Alex Washburn

Yesterday we planned to have breakfast in a cute town just outside Tegucigalpa Honduras and then make our way to a small town near the Nicaraguan border so we could cross early today. However, the gods of the Autopista had their own plans and although it wasn’t the worst possible day of riding it was probably the most dangerous day of riding we’ve had so far on this trip.

The road from Santa Lucia was beautiful and a great road although it gave us our fair share of problems. Photo: Alex Washburn

Santa Lucia (our goal for breakfast) is an adorable little town in the mountains just outside of “Tegus.” The town built into the green sloping landscape has a clean pond in the middle of it, a town square not much bigger than a basketball court, and a simple white church with a hilltop view of the valley that holds Tegucigalpa.

Unfortunately for us cuteness sometimes comes with cobblestones, which are murder to ride a bike on in Latin America. The stones are huge (typically much bigger than European cobblestones) so if one stone or a series of them have become seriously tilted it can throw your bike around. We finally found the correct cobblestone road out of Santa Lucia heading towards the hills and the rock quickly faded to a hard packed dirt road winding up and up and up.

Every once in a while we would pass a small grouping of houses or a few lonely chickens back-lit by amazing views. Dark green smallish mountains with fields and clouds and sunshine.

It was turning out to be a perfect ride, but around mile 20 there were some really deep indentations in the road from where water runs over the ground in rainstorms. I made it over them and kicked my bike down into first or second gear so that I could ride really slow till Nathaniel showed up again in my mirrors. As I was watching my mirrors I wasn’t paying much attention to where I was going and almost as soon as I saw Nathaniel appear in my mirror I felt my back tire start to slide out from under me in the gravel and I went down.

I clearly wasn’t hurt as you can see in the video and it only took us a second to get the bike back up, however once we did it wouldn’t start. At first I thought maybe the bike had flooded because some gas has started leaking out of it when it was on its side, but after letting the bike sit for several minutes and trying again that was clearly not the case. We decided the only way we were going to be able to get the bike moving again would be to try and roll start it down the hill.

In the process of pushing my bike up the hill and maneuvering it into position for our second attempt at a roll start, Nathaniel noticed that the back tire of his bike was going flat. When I couldn’t get my bike to roll start Nathaniel tried and got it running, which was awesome, however I was supposed to try and follow him slowly up the hill on his bike. When I threw my leg over it I realized his tire wasn’t just going flat – it was a pancake.

We spent probably an hour trying to fix Nathaniel’s tire, first using the goo we had and then plugs from a tire repair kit, neither of which were keeping air in the tire at first. We ran out of our compressed air and then I started asking people passing by if they had anything to inflate tires with in their vehicle.

I hailed a tuk-tuk driver over and asked him if he had one (assuming those little tires must have a lot of problems on these roads) and his passenger became very concerned for Nathaniel and I. We talked for several minutes about where a mechanic might be and how to get the tire inflated. The passenger ended up paying the tuk-tuk driver to take the boy he had been riding with back to their home and the tuk-tuk driver would then bring back something to inflate the tire with as he waited with us to make sure we were okay.

The man that stayed with us was incredibly nice. He was probably in his mid 50’s to early 60’s and he told us that although the area we were in was safe he wanted to make sure visitors to his country were taken care of. Although it’s not something that lives in our minds everyday, it’s worth mentioning Honduras is one of the most murderous countries in the world. It usually places in the top three in any given year above places like Uganda, Malawi, and the Congo.

The tuk-tuk driver returned in about 20 minutes and told us that after he filled Nathaniel’s tire we should follow him to a tire repair shop. He filled the tire from a hand pump and our friend that waited with us used pieces of plant alongside the road to stuff into the hole created by the nail Nathaniel had run over. I started up the road on Nathaniel’s bike after the tuk-tuk as Nathaniel roll started my bike and came after us.

When Nathaniel’s bike is on its’ center stand it is unbalanced and this is how the mechanics held up his bike as they fixed his back tire. Photo: Alex Washburn

The men at the shop charged us $15 for their help and jumped my bike with one of their cars before Nathaniel and I headed off into the night. We avoid riding at night because the roads here are sprinkled with nasty potholes and a lack of ambient light makes them a lot darker then in the US.

Getting back to Tegucigalpa was the worst 15 miles of riding we’ve had on the entire trip. With low visibility in the dark we couldn’t ride fast enough to keep our face shields from fogging and because it was raining they were also covered in water droplets so anytime we met oncoming traffic light would catch in the droplets on my face mask totally blinding me.

It took us a really long time to get back to the hotel we’ve been staying at in Tegucigalpa. Until we got back to the city center I was in a constant cycle of opening my face shield to vent it, wiping the water off it, flipping my mask up and squinting into the rain when cars came, flipping the face shield back down, praying during the moments I was totally blind on the road that I wouldn’t hit a pothole. Plus, I always worried that if I stalled the bike we’d be stuck along a dark rainy road in the middle of Honduras, without a way to start it again.

We’re now back in the same hotel we spend the last three nights and hope to figure out what is wrong with the bike today.

The Coastal Highway

Posted on November 21, 2013

This video was shot on the Coastal Highway in Belize, the road that all of the locals told us not to ride. I shot it all with a GoPro Hero3 silver edition and edited with the new GoPro suite.

Three Roads

Posted on November 20, 2013

Nathaniel prepares to record me crossing a bridge along the gloriously named ‘Coastal Highway’. Photo: Alex Washburn

It is impossible to get lost driving in the country of Belize. It’s tiny – at only 8,867 square miles in size it is barely larger than the state of Massachusetts.

In addition to this; a large percentage of this tiny country’s land is still untouched and they have minimal infrastructure. This has negatives and positives for the country as a whole, but what it meant for us as we looked at a map on Sunday is that there was only one obvious route to Placencia from Belize city and really only three major roads in the whole country.

A Canadian very familiar to the country had warned us about how terrible a fourth road (the coastal highway) was but we took the warning with a grain of salt because foreigners from first world countries sometimes have a skewed perception of what a ‘bad’ road is.

Sunday morning several Belizeans at our hotel confirmed that the coastal highway (which by the way is neither coastal nor an actual highway) was a terrible road. However – when we came to the turnoff where we could take the unpaved coastal highway or continue on the road most traveled we decided to have a little adventure (video coming soon).

We were on the coastal highway for less than 10 minutes and I could feel the smile slowly spreading across my face. It was rocky, dirty, muddy bumpy and everything our Kawasaki KLRs were meant to handle when we decided they were the best bikes for the trip. It took us 2.5 hours to drive 37 miles and it was fantastic (even if I tipped over twice and got super muddy).

A group of locals concentrates on their game of dominos in the shade next to the only gas station in Placencia Belize. Photo: Alex Washburn

As we attempted to leave we ended up hanging out at a gas station for about twenty minutes with some of the locals. I was feeling really dehydrated and I didn’t want to start the three hour ride to San Ignacio before drinking some water so we filled up and chilled out. The taxi drivers and gas station attendants were more than happy to let us share their shade and laugh at their brisk games of dominos.

Belizeans have been super friendly towards us no matter where we’ve gone. There were a lot of homeless people and panhandlers in Belize City, but everyone we’ve met from gas station attendants to hotel clerks, fellow restaurant diners and random people on the street have been welcoming and talkative. The men at the gas station accepting our presence so quickly is just another example of this.

The ride to San Ignacio up the Hummingbird Highway was the most beautiful stretch of road we’ve come across in Belize. The hills are so overgrown with palm trees, flowers and vines they resemble the scenery in Jurassic Park. The asphault on the “highways” is generally in great condition and it isn’t until you drive through the cities that you encounter insane potholes. I have never experienced potholes like they have in Belize.

They are epic pits appearing from nowhere waiting to swallow your front tire whole. In many places swerving around one hole just dumps you right into another so it’s best to just ride straight through and try not to break your teeth as you grit through it.

When we arrived to San Ignacio we had our first meal of the day at Hode’s where this flute player provided the soundtrack. Photo: Alex Washburn

Our bikes parked in front of Hode’s restaurant in San Ignacio Belize. And yes – that is a giant red umbrella attached to my bike. Photo: Alex Washburn

We are both eager to (hopefully) cross the border into Guatemala after our appointment and continue our adventures in Spanish speaking Latin America.

RECOMMENDATION: If you are riding bikes from the US through Latin America it might be hard to get your bike serviced in Mexico depending on what you are riding. If you come to Belize – Motor Solutions in Belmopan is a well stocked shop that should be able to help you out and English is the official language of Belize which should be a relief if you don’t speak spanish.