Where the Autopista Ends

Two motorcycle bloggers in the San Francisco Bay Area.

The swing…

Posted on February 1, 2014

…at the end of the world.

On a mountain, above a sleepy town nestled in the mist of the Andes laying in the shadow of a volcano, waits a man. He listens to wind, feels the restless earth, and is every watchful of the volcano, a constant guardian of the city and a very special swing.

Dangling from La Casa Del Arbol, a house in the only tree on the mountaintop, is the swing at the end of the world. Travelers have been known to come, from far and wide, to swing over the edge and see what their destiny holds. Whether it is the thin mountain air or the rush of going over the edge, many have left the mountain changed.

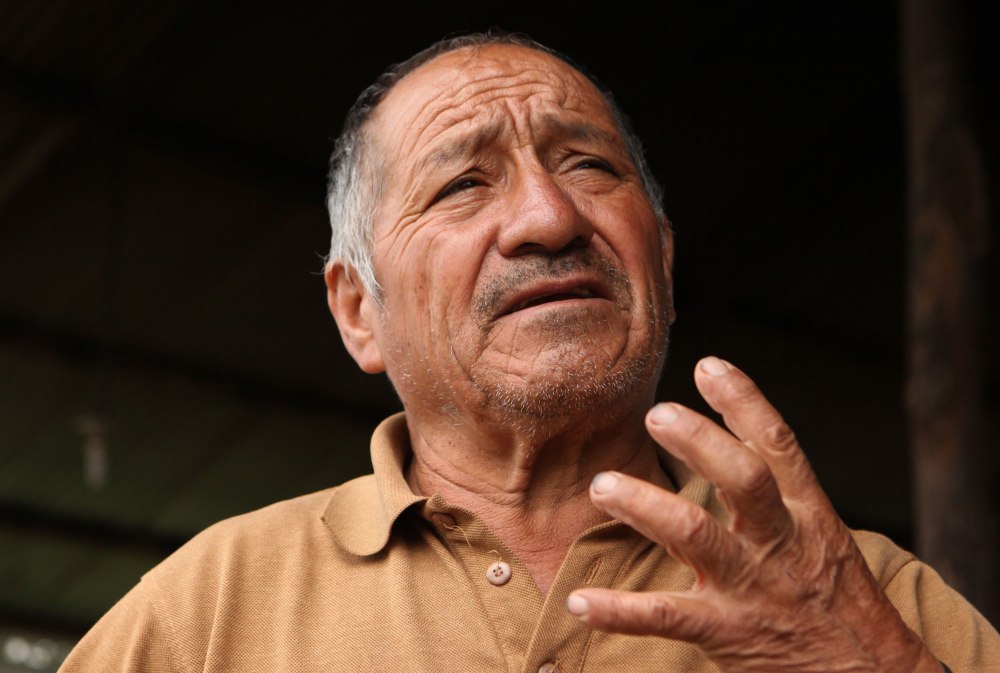

Carlos, the volcano watcher, never swings. He sweeps the grounds, herds his two cows, has family visit once a week, but he never swings. He smiles at the weary travelers, as they appear out of the mist and then dissolve once more into the quiet countryside, but he never swings.

The travelers donate what little they have to help maintain the swing of their dreams, that others may come, as they have, to see into their futures. Carlos replaces nails, tightens loose rope, and checks the foundations of La Casa Del Arbol, but he never swings.

Carlos talks about his life living on the mountain watching the volcano above Baños Ecuador. His family visits him once a week (on sundays) but other than that his everyday company are his two cats, two cows and the tourists that float through. Photo: Alex Washburn

Occasionally he will talk to one of the travelers. He tells of the volcano and of the house, but rarely of the swing. To those he likes, he invites them to leave a message in his journal, for the lonely hours he spends on the mountain, watching the volcano, but he never swings.

For those who will come and those that have gone, their paths were their own. But for Carlos, he is the watcher of the volcano and the guardian of the swing at the end of the world. That is all he needs to know. So let others come and swing, he is fine smiling and watching and guarding.

(The above is just a fictional interpretation of Casa Del Arbol, feelings that I had while we were there. Carlos is real, he is the old man that watches the volcano and signals others if there is activity. He does have a book he invites some to write a message in for the long hours on the mountain and his family does only come once a week to visit him. He is the guardian of the swing at the end of the world. –Nathaniel)

The land of Piñas and Topes

Posted on November 7, 2013

One of the tidbits of knowledge that Ceasar (Alex’s cousin) passed onto us, well mostly for me, was that the country between Tuxtepec and Villahermosa could be considered the Land of Pineapple’s. Through Alex’s translation for me, he said something akin to “pineapples as far as the eyes can see” with a motion of the arms encompassing a wide circle.

Once we had chosen the northern road out of Oaxaca, it was predetermined for us that we would pass through the land of piñas (where you could get a bottle of fresh squeezed juice for a $1.00). Getting a later start than normal to the morning, we headed out of Tuxtepec, at fifteen miles an hour.

Tuxtepec is not the center of the universe in Mexico, and once you get on the back country roads and highways of Mexico, they run right through towns, literally. The way that they ensure the safety of the people in those towns is to construct topes (speed bumps) of varying sizes and inclines. Alex hit one of these going out of Oaxaca hard enough to make her think that she might throw-up. Anyway, going along to Villahermosa was filled with tope after tope, which makes for tiring driving as you never really get up to cruising speed for long (plus if you don’t see the tope, it can make for a jarring experience).After stopping for some breakfast/lunch, Alex had me lead for a while and gave me instructions to stop at a pineapple stand that looked good. We got about fifty miles down the road, and I started sweating thinking I had missed the last one, when all of the sudden, like an oasis in the desert, a stand appeared in the distance with more pineapples than you can fathom.

Women stood in the road selling bottles of sweet, golden nectar while an older husband and wife stood in a shack on the side of the road crushing pineapples. I knew this was the place, the land of the piñas, and we pulled over, took our jackets off and picked up a bottle of fresh pineapple juice for a mere $15 pesos.

Imagine being able to stick a straw into a pineapple and drink the juice straight out of it. That is what it tasted like. Alex commented:

“You may never have pineapple juice this fresh ever again.”

It made the moment even more poignant. Sitting in the shade, the sun high in the sky and burning, the juice was as sweet and tangy as I had hoped, and it fueled us better then any Gatoraid could have (I am sure it had more sugar then two cokes together, but it was delicious).

Portrait of a Piña vendor along Highway 145. They juice it, bottle it, ice it and sell it the same day. Photo: Alex Washburn

With our thirst quenched, we continued on toward our goal of Villahermosa. About fours hours into the riding of the day, the tope spotted landscape gave way to toll roads of US quality freeway status and we started to gain some distance.

We stopped for gas about an hour out of Villahermosa, and as we started to exit the Pemex (which I think are the only real gas stations in Mexico) I saw the sheen of water on the freeway. Not thinking too much of it, we both continued over it, and that is when I grasped our mistake. Alex made it across but as soon as my front tire hit the liquid, I began to skid and to my horror realized that the substance was oil.

As in all life situations where you brush against true adrenaline producing moments, time slowed down and I remember thinking clearly that I wasn’t going to be able to keep the bike up, that I was going down. The next thing I knew I was on the ground, and then I was up again, my muscles moved faster then I could think, and I was trying to lift my bike up, slipping in oil that covered a wide expanse of pavement.

It was a river.

Nathaniel does a systems check on his bike (and himself) after a car accessories vendor helped him to an oil free stretch of pavement. Photo: Alex Washburn

Luckily for me a guy came running up and offered a hand to get the bike up (Alex was able to stay upright, but couldn’t park her bike in the mess) and helped me get it over to the side of the road ahead of Alex. I thanked him as he ran off, maybe he was a guardian angel because he was gone even as quickly as he had shown up, and I assessed the damage. Other then some new scrapes to the panniers and my handle bar protecters, the bike was no worse for the wear.

Even a couple days removed, my heart still starts pumping when I think about this, but thankfully we were both going slow, and there hasn’t been any lasting damage to the bike (it fired right up once we got the situation under control). Furthermore, there was no bodily damage, I was completely protected by my equipment, I wasn’t trapped under the bike (thanks to the panniers), and the riding gear has paid off in my opinion. I now know what riding in oil is like, and I avoid substances on the road, even if they look like water just to be safe.

We barely made it to Villahermosa in the last lingerings of the day, and with heavy traffic leading into the city, pulled off at the first decent looking roadside motel for the night. If it wasn’t for the piña juice I might not have made it.The next day was more riding, heading north, I distinctly remember getting the smell of salt in my nostrils and knowing that the ocean was near. I grew up in Santa Cruz, and while I may not have appreciated it then, the sea has a claiming effect on me that makes everything feel right with the world.

“How can things be bad if your by the ocean?”

We rode the whole day, along coasts lined with palm trees and fisherman. The final rays of the sun were fading over the water as we rode into Campache. It is the capital of the state and you can feel the forced jubilance it emulates for tourists in its historic district. For us it was just a hotel room, a warm shower, and a place to hang our helmets for the night. I am sure it is an amazing town, but we wont know on this trip.

Our days in Mexico are numbered, tonight we are sleeping in Merida and we plan Chichen-itza and a cenote (sinkhole) in the coming days, more adventures to come.

Days of the Dead

Posted on November 5, 2013

A man dressed in drag dances and poses in the lights of a police vehicle as residents The residents of Tule Mexico exit the city cemetery following a dance part on November 2, 2013. Photo: Alex Washburn

Alex did a pretty good job of filling everyone in on what was going on in Oaxaca for day of the dead (in fact there are multiple days of the dead, with one big celebration at the beginning for All Hallows’ Eve). It begs to be mentioned that for every flash happy maverick we saw in the cemeteries, there were plenty of tourists being respectful of the families and celebration (though there were a crushing amount of tourists).

On Friday afternoon we got back from Tule cemetery and having been out late the night before, going to three cemeteries for Day of the Dead, we thought we’d just spend the night in. However, someone was going around the hostel promoting a cemetery tour that night that would go to a couple of cemeteries we hadn’t been too.

We said yes and signed up, and only after did I find out it didn’t start till 8:30 and was a five to six hour tour (you read that right) meaning it wouldn’t be over till one or two in the morning. I almost ducked out at the last minute before the tour started, and after what was to come, I wish I had.

The tour was the worst both Alex and I had ever been on for a multitude of reasons. The person conducting the tour (asshat) hadn’t done any research and half of the cemeteries we went to ended up being closed for the night by the time we got there. Of the two we did visit, one was Tule (where we had just been earlier in the day) and the other was the main cemetery in Oaxaca (where we had been the night before). While touring the two cemeteries we did go to, the guide didn’t offer any insight or knowledge of what was going on and I honestly think Alex and I know more about Day of the Dead than he did.After leaving the main cemetery at 11pm, we then proceeded to be dragged from closed cemetery to closed cemetery until finally at 1am, the tour asked for the guide to just take us back to the hostel (where he informed us he wanted to take us to one more place that was supposed to be happening, we didn’t bite). Once returned, he offered us a free tour the next night, but we all declined citing other plans. I could think of nothing worse then to have to relive that experience again. I would pay money to not have to go a second time.

We spent the last night touring the celebrations in Tule and Oaxaca, which is where I met a posse of drag queens and was escorted around town. The next morning it was time to pack all the gear, load the bikes and head on out to the gulf coast.Alex’s cousin (who is a truck driver) told us that there were three options out of Oaxaca: 1) was a pleasant, but relatively boring back-track, 2) was over 200 miles of hairpins going kind of the wrong direction, and 3) (the one we picked) was just over 100 miles of s-turns with gorgeous views and a nature reserve.

Heading out of Oaxaca and into the mountains, it was all climb for the first two hours of the ride. What had started as a warm, muggy day in the valley quickly turned into a chilling, foggy climb where at one point we broke through the fog (yes literally climbed above the clouds),

before descending once more into the mist. However, about right at the halfway point, the road circled the mountain and started heading down and we were suddenly in the middle of the nature reserve complete with roadside waterfalls.If you are ever in the Oaxaca region with your bike, you have to take the road from Tuxtepec to Oaxaca (hwy-175). Make sure your bike can handle the mountain terrain, but the views you get will be some of the best anywhere. We finally made our final descent, and rode on to Tuxtepec for the night.

Oaxaca

Posted on November 2, 2013

Martin Santiago Lopez plants marigolds for day of the dead on the tomb of his grandfather as his mother watches in the cemetery of Santa Maria del Tule, Mexico. Most of their family buried in the cemetery and since the family trade is landscaping they use a lot of plants in their Dia De Los Muertos decorations.Photo: Alex Washburn

Oaxaca is a fantastic city. It’s known for so much I might pity its advertisers when they need to select what to highlight for the city and state. Do you gush and rave about the food? The diversity of languages and cultures? The handicrafts? The scenery? The architecture?

In the months leading up to October 31st, November 1st and November 2nd most of the hype seems to be about the Dia De los Muertos celebrations that the city and surrounding areas immerse themselves in. But, I’ve noticed a shift in the atmosphere in the three years since I last visited Oaxaca for Day of the Dead.

More tourists and more Halloween.

As someone recently told Miriam Jordan for the Wall Street Journal:

It’s not mexican halloween.

But as awareness of Day of the Dead spreads through the United States and beyond I believe we are going to see more and more candy corn and Jack-o-Lanterns creeping into the holiday.

People walk past graffiti protesting the Halloween-ization of Dia De Los Muertos. Photo: Alex Washburn

Day of the dead is something even the Spaniards couldn’t destroy but how will it fare against Disney?

As I feel my anger building on the subject I have one memory playing over and over in my mind. A little old woman hunched over in the Xoxocotlan cemetery surrounded by a half dozen people popping flashes at her. One woman (who told Nathaniel she was a hobbyist being escorted through the Dia De Los Muertos festivities by a National Geographic photographer) had a remote flash that she worked that little old woman over with for at least 30 minutes. And I don’t mean one shot every few minutes – I mean celebrity style motordrive shooting at times. At one point she even placed the flash on the grave the woman was mourning over.

I asked the woman’s family member (I assume daughter) if the photographer had asked to take her photo and she said no. I asked her if the old woman was bothered by it and she said yes and explained that was why the woman had stood up and turned away from the cameras for a while. I offered to intervene for them because the photographer didn’t speak spanish but she said it was okay and thanked me anyway.

We stood and watched horrified by it… we think she was with a Photo Xpeditions Tour .

The hobbyist photographer was certainly more aggressive than most but at times it seemed there were more tourists and TV crews present than locals.

Four photographers focus on one woman in the old cemetery of Xoxocotlan. The photographer to the far left used a remote flash on her for at least 30 minutes. Photo: Nathaniel Chaney

I might be a hypocrite for allocating so much space to complain about the effects of tourism when I myself am a tourist. But, I think people need to use more common sense when they try and absorb the traditions of other countries.

How would that photographer feel if someone she didn’t know accosted her the same way? Someone she couldn’t talk to and was maybe a little afraid of?

Every photo you see in this blog post of someone in a cemetery I either had a very lengthy conversation with (see photo at the top of the post) or a short exchange with to assess wether or not they were okay with my camera and I being present (see photo below).

A young boy lights candles with his sister and grandfather in the main cemetery of Xoxocotlan Mexico in observance of Dia De Los Muertos. Photo: Alex Washburn

Our first day out for Dia De Los Muertos Nathaniel and I went to three different cemeteries – one of which was during the day for both of us and another I visited during the day alone and took Nathaniel back to later at night.

For me – the sweetest memory so far has been standing in the cemetery of Tule with Martin Santiago Lopez and his mother and learning from them about their town’s history and the people they loved that are now buried there. I was hesitant to speak to them at first, but when I saw them openly engaging with some other daytime visitors I approached to strike up a conversation.

They were incredibly welcoming to me (and my camera) and told Nathaniel and I to come back to Tule today (Saturday) for their town’s big party in the afternoon, which we intend to do.

The photos do not have the soft romantic glow of like the other images I took later in the night but they are authentic images of wonderful people freely giving permission to be photographed by the only camera in the cemetery, which to me is more ideal than candles and a solitary figure hunched over hoping I will go away.

The second night we decided to take a tour and see if it was surprisingly insightful or as terrible as we feared, but Nathaniel will tell you more about that tomorrow.